INTERVIEWS WITH AUTHOR PHILIP ROY

(including text, radio and video links!)

Listen to this Performers Podcast interview, (formerly called “The Inadequate Life”), with Philip and renowned Canadian podcast host, Keith Tomasek. Learn about Philip’s creative inspiration, among other things. Here’s the link: https://theinadequatelife.libsyn.com/author-philip-roy

Listen to this Performers Podcast interview, (formerly called “The Inadequate Life”), with Philip and renowned Canadian podcast host, Keith Tomasek. Learn about Philip’s creative inspiration, among other things. Here’s the link: https://theinadequatelife.libsyn.com/author-philip-roy

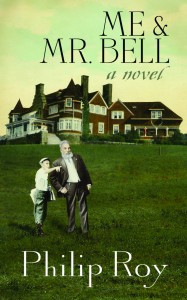

Listen to Philip’s October 16, 2013 interview with CBC Radio. Among other things, this interview focuses on the latest “chapter” in the Page Turner Project and Me & Mr. Bell. Just click on this link.

Check out Philip’s video interviews with Cape Breton University Press:

Check out Philip’s video interviews with Cape Breton University Press:

Cape Breton University Press features six segments of an interview with Philip about the writing of Blood Brothers in Louisbourg in addition to a reading. Each of the links below connect with CBUP’s YouTube channel.

On interpreting history in a fun way: http://youtu.be/sIQamtqJZRw

On writing “beyond the storyline”: http://youtu.be/5Avz2bjocRY

On the background for his characters: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q-DAO62VJhY

Philip reads from Blood Brothers in Louisbourg: http://youtu.be/_0uBjQwspjQ

On a possible sequel: http://youtu.be/jjYkOi3oQnI

Learn about Philip’s other creative talents: http://youtu.be/LQqcLMIcLRI

On the talents of the young writers he meets in his writing workshops: http://youtu.be/_uZ56aFJxWk

Listen to Philip’s November 13, 2012 interview with CBC Radio and learn about The Page Turner Project with CBU Press. Click on this link to hear the interview.

Listen to Philip’s November 13, 2012 interview with CBC Radio and learn about The Page Turner Project with CBU Press. Click on this link to hear the interview.

Interview with Cape Breton University Press

Interview with Cape Breton University Press

Philip Roy, author of Blood Brothers in Louisbourg, talks about writing Blood Brothers, the need to be creative on the fly, and the magic of the past. You can pick up a copy of his newest book directly from CBU Press or at gift shops and bookstores throughout Atlantic Canada (and beyond).

September 27, 2012

Why did you choose to set a novel in Louisbourg?

I first visited the site of the fortress as a child, and often afterwards, and many times as an adult. I watched the remarkable transformation the reconstruction created. It always seemed incredibly special to me, like a kind of miracle even. The fortress of Louisbourg has always sat in a special corner of my imagination. Any opportunity to set a novel there was irresistible to me.

Did you visit often while you were writing and, if so, how did it influence your writing? What are your impressions of Louisbourg before and after writing Blood Brothers?Rather ironically, I didn’t visit the fortress while I was writing this book. But I felt I had a sharp memory of the buildings and their interiors. I felt confident. And then I was always consulting books in my research. This past summer, I visited for the first time in several years, and experienced a kind of shock. I realized I had strayed too far from reality in my mind’s vision of the place. I had put kitchens in the wrong rooms, rooms on the wrong floor. Rooms were bigger and smaller than I imagined them. Long-time characters in costume weren’t there anymore—the wonderful bossy French woman who served food and always told me to tuck my napkin in tight and sit up straight. The man in the Engineer’s house who spoke in a whisper. I was a bit disoriented. I was carrying the book in my head and had to let it go. I love both the book and the place. But they are not the same.

Tell me a bit about the characters. Why did you choose two guys and a girl?

The two guys are fantastical extensions of me, I suppose. I’m a musician (my favourite composer is Bach), and a bookish type (I think). Pacifism appeals to me, though not exclusively. I would always fight to protect. On the other hand, though I cringe to remember it now, I hunted as a teenager, and often slept outside in the woods in winter. I still run in the woods almost daily, and love nature at the depth of my core.Celestine’s character is more difficult for me to explain. When I remember being fifteen, it starts coming back to me.

Perspective is really important in this novel. Can you tell me a bit about that? Why did you choose to write one narrative in the first person and one in the third person?

The short answer is that I fiddle around and see what feels right. I have set Two-feathers up as an ultimate, selfless hero. I felt this was communicated most effectively in the third person. Jacques’ angst over his father and his self-reflection seemed best served by first-person expression. Interestingly, I’m working on the sequel presently, thirteen years on, and Jacques’ presence in the novel is expressed through third-person. First-person perspective goes to his nephew, a pugilistic, seriously chauvinistic, fifteen-year-old badass.

One review of Blood Brothers said the characters’ stories “end too soon” and that the conclusion “leaves the readers with too many unanswered questions.” Why did you choose to end the book where you did?

It never crossed my mind the tale might end too soon. When you write a book, it feels endlessly long. Then people read it in a few hours. It rather cuts you down to size in a hurry. I do remember thinking that teens wouldn’t want to read a long book, but maybe I was wrong. Well, it seems some do, and some don’t. Same with reviewers. I always try to do my absolute best, length included. Leaving things unanswered sits better with me than many others, I realize. I’ll try not to do that too much. It does seem to irk some people. I have always preferred tales that leave you wondering about some things. And now that I’m writing a sequel, it serves me well to have left certain things hanging in the first book. That wasn’t intentional, though.

Are you hoping to accomplish something by writing historical fiction? What are you hoping young people will take away from your novel?

Oh, yes! I love history immensely, and want to share the richness of it with young readers. If I can inspire any young readers in any way, I will feel incredibly gratified. Of course, I remember having been influenced by and swept away by the magic of tales of the past, as if the past were a magical world that exists at the same time as us, but somewhere else, which maybe it does.What I hope young people will take away from this novel is a discussion of pacifism in their own minds, and perhaps also an understanding of the causes and purposes and results of war. Also an increased awareness of the people who came before us, who lived where we lived, and died where we will die. Becoming more aware that we are a kind of link in a chain, historically speaking, is good for us, I think. I believe we know ourselves more deeply this way. I also hope they will come to enjoy reading more. And should any young reader venture to listen to Bach because they read my book, I’ll be thrilled.

The book’s becoming a movie and it’s being translated into French. What are your thoughts on this? How do you feel about it. Any anxieties?

I’ve heard that ninety percent of books optioned for film never get made. So, I don’t hold my breath. Having said that, I’d be so excited, I’d probably dance. I’d also beg to be in the film, you know, in sneaky cameo roles like carrying cannonballs around or raking the field.I cannot express how pleased I am the book will be translated into French. It is such an honour for me. I suppose it is only fitting, in a way. I feel no anxieties. I wish my father and grandfather were around to see it.

You give a lot of workshops teaching kids how to read and write. Did you take any workshops yourself? What writers or teachers did you learn from or were inspired by?Strangely enough, I was particularly unlucky in never having had an English teacher with whom I related well, or from whom I felt I could learn much. It was the opposite with my music teachers. They were fiercely strict and demanding, but also warm on occasion. I was lucky in that they were especially well trained themselves, knowledgeable, and proficient. I learned all the important lessons through my music teachers and sports coaches.It seems to me there are two schools with regard to writing workshops: those who take them, and those who don’t. I fall into the latter group. When I give workshops myself, I am more concerned with a student’s sense of self-affirmation and personal motivation than actual skill. Any skill can be developed once one believes in oneself. I really believe that we actually always teach ourselves. Perhaps teachers teach best by showing us how to get out of our own way.

(Editor’s note: Philip Roy is the author of the best-selling Submarine Outlaw series. He travels extensively to schools, fairs and festivals and carries with him a model submarine and helicopter made with found objects.) What inspired you to build your submarine? And the helicopter? And the shark? Any other current projects on the go?

I just love building things. More and more of the people I meet these days—older writers and artists in various fields, especially—demonstrate for me how our creativity grows as we do, and it has an inclination to spread if you let it. As a good friend (and very busy writer) recently said to me, “The important thing is to be creative.” On the other hand, I find it harder and harder to find the time, so that I’m always having to become more flexible, to create on the fly, so to speak. There is a particular pleasure in seeing a physical creation take shape. And for me, it is particularly exciting when it is put together out of random pieces of stuff I gathered here and there. I really want to build an octopus!Now I am getting really bold and am composing a “Fantasy for Submarine Outlaw.” I’ve already composed a Fantasy for “Train Riding Through Wintery Farmland.”

You’re a classically trained musician. You mentioned that your writing has allowed you to compose more recently. Does the opposite occur? How does (classical) music influence your approach to writing?

Honestly, it was the discipline of classical musical training that enabled me to do pretty much everything. It was so much work to learn to play difficult classical pieces, and the memorization of a body of work, especially, is a kind of training for the mind that is simply invaluable. I’m guessing it might be like playing chess without a chessboard. Once you have this kind of power of concentration, you can write essays while you’re out walking or running, construct stories or even sculptures or compose music. The structure of music, such as the counterpoint in Bach’s fugues—and I play them daily—helps me be more aware of the various elements that must come together in a story. Structure is always a challenge.

Tell me about Cape Breton. What are your favourite things about the place? How often do you go there? What do you love about it? When you go there, where do you go and what do you do?

I love that Cape Breton is an island, and that it is a very Scottish place. I associate it with nature, trees and wood smoke, beautiful drives, and beautiful views. I also love that it is an incredibly creative place, although, sadly, too much of its talent goes away, and only sometimes comes back. That’s the harsh reality of economics, although I truly believe that with the way technology has of shifting economic centres, and giving individuals increasing freedom and control of their means of production, places such as Cape Breton will grow economically at the expense of places out west. That’s just my personal belief. I’m in Cape Breton several times a year, more some years than others. Usually for work, or to meet with friends.

What are you reading right now?

French. I’ve got a big challenge ahead with becoming bilingual. I’m also always reading non-fiction to be able to write fiction. I have been reading Nelson Mandela’s Long Walk to Freedom, which is long to read, too. I started it on a 27- hour train ride between Johannesburg and Cape Town last spring. I have just finished Charlotte Gray’s awesome Reluctant Genius, about Graham Bell. As with most of what I read, these are preparatory to writing novels.

Interview with Laura Bast

Interview with KeenReaders–Meet An Author

August 2, 2012

Q. How keen a reader were you as a child?

A. I was intensely keen for short bursts of reading, but very unlike the kids who read so voluminously. I didn’t read voluminously, but read with the kind of intensity one has when one discovers a secret cave inside a mountain. Sports and a deep love for the woods and outdoors kept me pretty occupied. I did, however, take a volume from the encyclopedia to bed with me every night, and would often fall asleep in the middle of a page.

Q. What were your favourite reads as a child?

A. It is easy to say: The Box Car Children. It really swept me away. So did a trilogy of books on archaeology my mother bought me one year. They were about ancient Egypt, the Vikings, and cave men. The lines between fiction and non-fiction were quite blurry to me as a kid. Once again, the World Book Encyclopedia came to bed with me every night. To this day, I still must resist starting sentences with, “Did you know that . . . ?”

Q. What made you a keen reader (or are you)?

A. Habits acquired in youth linger. I’m much the same as I was—I read non-fiction to write fiction, and the lines between the two are still blurry. When I observe friends and acquaintances who read an incredible amount, I cannot call myself a keen reader. And yet, my relationship to reading runs very deep. It has been profoundly affected by my becoming a professional writer, however. Perhaps a certain innocence has been lost. It isn’t often I can avoid the urge to reconstruct what I’m reading, and that can be distracting.

Q. When did you first decide that you wanted to be a writer?

A. In truth, I wanted to be a writer in junior high school, especially in grade 7. Then it left me until I was 31, and had finally recognized that I wasn’t going to make it as a classical pianist and composer. Now that my writing career is progressing well, I have recently returned to composing, so I’ve got the best of both worlds.

Q. What have you learned about reading to kids, and how did you learn it?

A. The experience of reading to my own kids was almost as profound as learning to read for the first time. With my own kids, I received a more thorough exposure to kids lit, especially at the elementary level. This had a direct effect on my becoming a children’s author. Reading to kids in schools and libraries became a confirmation that I had found my proper calling in life. This interaction with young readers and writers directly infuses my work and sense of community and purpose. I can honestly say it is the best job in the world.

Q. What’s your best advice to parents of teens or pre-teens to help their kids to read more?

A. I have long been a strong advocate of recognizing the uniqueness and individuality of our kids’ interests and processes. What works so wonderfully for our eldest child might fail utterly for the next. One reads all the time; another never does. My best advice is to appeal not only to the specific interests of each child, but also to the particular way that he or she enjoys reading, whether in large or small, or even tiny, doses. I know some parents who were so discouraged at their kids’ appetite for video games and aversion to reading, only to discover to their surprise how extensively their kids were reading in the course of playing the games. After a trip to the bookstore, they returned with a large volume concerning everything about video games, into which their kids delved like tadpoles dropped into the lake. I do subscribe to the view that any reading is good reading and will lead to greater and greater things if encouraged.

Q. What do you most enjoy when you’re not reading or writing?

A. Running and hiking in nature and composing music. My best ideas for stories always come from being in nature. At the same time, so many years of learning how to write have somehow opened up the world of music composition to me in a way I never imagined possible. Like many kids I meet, I always wanted to find myself on a kind of magic carpet in life, to really discover secret treasures and experience magic. Now, I can honestly say that that is exactly what I feel in this wonderful world of creating stories and music.

10 Questions with Philip Roy

10 Questions with Philip Roy

September 13, 2010 by Woozles Bookstore

It has been a while since I’ve read a book cover to cover. Probably the last was Jacques Cartier: Navigating the St. Lawrence River. Most recently I’ve been reading, and loving, Robert Weston’s Zorgamazoo, which is wonderful and amazing. I met him last month and he is wonderful too.

What was your favourite book growing up?

Well, I remember The Box Car Children sweeping me away. I also had a trilogy of books about archaeology that I read over and over and over and over…

What literary character do you most relate to?

Hector. The oldest son of King Priam of Troy, from Homer’s Iliad. Hector was the greatest Trojan warrior. He was also a great dad and a wonderful husband, and a loyal son. He embodies all the virtues I think a man should have. Someday I intend to re-write the story of the Trojan War, and I’m going to have Hector kick Achilleus’ butt all over the plains of Troy.

“Call me Ishmael…” Name that book.

That’s Moby Dick, I think. Do I win?

Describe your ideal day off.

What is a day off? I fill every day with things I love to do, like running in the woods, eating yummy things, day-dreaming, playing piano and the fife, and …oh yes, writing. But I must admit, days spent exploring new places are very special.

If you could attempt any profession but your own, what would it be?

Hmmmm, I think it would be amazing to be a counselor. I love to hear about peoples’ lives and it would be very meaningful to be trained to be able to help people with the difficulties that life often brings.

What would your pirate name be?

“Somethingnasty.” People would stare and ask the other pirates, “Who’s that?” And the other pirates would say, “Oh, that’s Somethingnasty. Don’t get too close!!”

What is your favourite word?

Sanctuary.

Who do you want to be when you grow up

?If I ever do, I want to be Rudolph the magician, who can fly.

What is a Woozle?

It’s a little furry thing that comes in a cereal box.

Please e-mail Leila at leilamerl28@gmail.com if you’d like to be added to our digital mailing list. (We’ll contact you whenever new titles are out!)